Sculpting Wool, Shaping Identity: A Conversation with Jessica Costa

Born in São Paulo and trained in fashion and textiles, Jessica Costa weaves together ancestral techniques and contemporary narratives to challenge the boundaries between art and craft. Her vibrant, sculptural works blur the lines between tapestry, painting, and sculpture—amplifying feminist histories and overlooked labor. In this conversation, she reflects on her Brazilian heritage, her creative process, and what it means to reclaim textile as both language and resistance.

Can you tell us about your journey into the world of textile art and

craftsmanship?

I've always been fascinated by working with my hands. As a child, I would watch feminine TV shows focused on crafts and DIY projects in the evenings with my mom. With a background in fashion, my first approach to textiles came through fabric as a starting point for creation, a surface waiting to be transformed. I was especially captivated by the possibility of constructing something from a material as humble as yarn.

This curiosity led me to explore various textile techniques like knitting and embroidery, skills I developed alongside my academic studies in fashion and textiles. I was struck by how these ancestral knowledges have historically been passed down in domestic, often feminized spaces, and how even today they remain at the margins of formal education. That tension stayed with me.

I eventually began teaching these practices, but the true shift happened when I started investigating how textiles are situated in art history, and how this conversation often intersects with gender and social narratives. That’s when I understood that my work could inhabit this space in-between, questioning the divisions between art and craft, and embracing this contradictions and richness that come with blurring those lines.

How did your upbringing in Brazil influence your approach to materials and textures?

Brazil is a vast country with rich and diverse cultural traditions. I was born and raised in São Paulo, a fast-paced and complex city shaped by a cultural patchwork, a mix that also defines my own background. My family has roots in Pernambuco, in the Northeast, and throughout my life I’ve been surrounded by people from different regions and cultures. I see myself as a result of this heterogeneous blend, which naturally influences my way of creating.

This diversity led me to choose textiles as my main platform, a space where I could merge contemporary aesthetics with ancestral techniques. Living in a chaotic urban environment while working with slow, artisanal processes creates a kind of tension that I embrace. It feels like a subtle form of resistance and reflects the value I see in local craftsmanship.

The forms in my work don’t seek to represent an external idea of Brazil, but rather emerge from an internal, emotional landscape. Still, the vibrant colors I use often resonate with broader perceptions of Brazilian culture. While that can border on stereotype, it also speaks to the deep presence of color in our everyday life: in nature, festivities, and popular culture. I work with 100% natural Brazilian wool as a way to support local industry and remain rooted in the material reality of where I come from.

What were the first materials or techniques you experimented with as an

artist?

My practice began with knitting, especially domestic machine knitting. I developed my early works with this technique, and later transitioned to tufting a technique that, for me, disrupts conventional associations between textile work and notions of delicacy, containment, and femininity.

The physical gesture of tufting (using a gun), which produces density, weight, and volume in the fabric, introduces a dimension I find conceptually rich. It allows textile to move beyond the surface, asserting presence and occupying space with sculptural ambition, which has led me to increase the scale of my work.

Through this shift, I found a way to confront and expand the gendered narratives that have shaped how textile practices are perceived and valued within the art world.

Can you walk us through your creative process from concept to final form?

Throughout each stage of my work, I try to bring gesture and intention to a technique that inherently involves repetition and rumination.

It begins with hand-drawn sketches that combine abstract shapes with anatomical references and memories. I study weight, composition, and how gravity might act on the forms, giving them a sense of presence and vitality. Then I move into a color study, sometimes using painting, sometimes digital tools, always with brushes that simulate texture to approach the composition pictorially, like a painting.

Next comes the technical phase. I transfer the drawing to the fabric at full scale and begin tufting. An interesting aspect of this technique is that it’s done from the reverse side, so the entire image must be mirrored. I use my earlier studies as guides maps that I can follow. When blending colors, I usually follow a more fluid, painterly process.

Finally, I move into the part I enjoy most: sculpting the wool. Through carving, I shape the surface, adding volume and complexity. The final step is finishing, hiding edges, refining details, and vacuuming the piece, which can be time-consuming but it’s an essential part.

Your works seem to blur the line between sculpture, tapestry, and painting. How do you define what you do?

Some people define my work as art, others as craft, but I intentionally identify myself as an artist-artisan, deliberately invoking the full weight of these terms and how they have been treated throughout art history. For some, this might seem redundant; for others, it may suggest contrast or even opposition. It is precisely this friction that I seek to activate.

This approach questions both roles and blurs the line that supposedly separates them, if that line even exists when we engage in the act of making. My work is strongly grounded in three pillars: sculpture, tapestry, and the pictorial.

Perhaps this separation doesn’t exist in practice, but in terms of paradigms and the canon, it is real and cannot be ignored. It shapes how art history is understood and how we interpret it today. Still, I enjoy inhabiting both positions and embracing that duality.

What role does color and texture play in conveying emotion or narrative in

your pieces?

Color and texture are, for me, the strongest elements that define my artistic language. Describing my use of color in words can be challenging, as it’s a subjective and intuitive process that comes from observation: from my surroundings and from the conceptual direction I project onto each form.

Working with industrially pre-dyed wool yarns, I can’t mix pigments as in painting, so one of my main challenges is to bring a pictorial approach to the material. I do this by layering threads gesturally, blending tones, and creating optical effects and depth.

Texture, on the other hand, emerges as a sculptural exercise, it’s where I shape the narrative through carving. I build forms that are often amorphous but evoke a bodily or human presence. Inflated and fragmented shapes emerge as sensitive extensions, expanding bodies that resist control, that don’t fit into molds.

These forms resonate with the experience of the female body in the world: historically seen as excessive, inappropriate, or out of place.

How did it feel to be selected as a finalist for the LOEWE Craft Prize 2025?

For over a decade, I’ve been dedicated to manual textile techniques, so receiving this recognition from the LOEWE Foundation, an institution that celebrates ancestral and handmade craftsmanship, is deeply gratifying, especially being part of a group of incredible artists from all over the world.

In this edition of the LOEWE Craft Prize, I’m the only finalist from Latin America and the first Brazilian woman ever shortlisted. Carrying that with me is both an honor and a profound responsibility. I walk a path shaped by many hands before mine. I’m just a small fragment of the immense richness of craft and manual work that exists across Latin America and in Brazil.

I hope my presence helps amplify the voices of other Brazilian artists, showing how powerful and relevant our local production truly is.

Can you tell us more about the work you presented for the Prize—its meaning,

materials, and how it came to life?

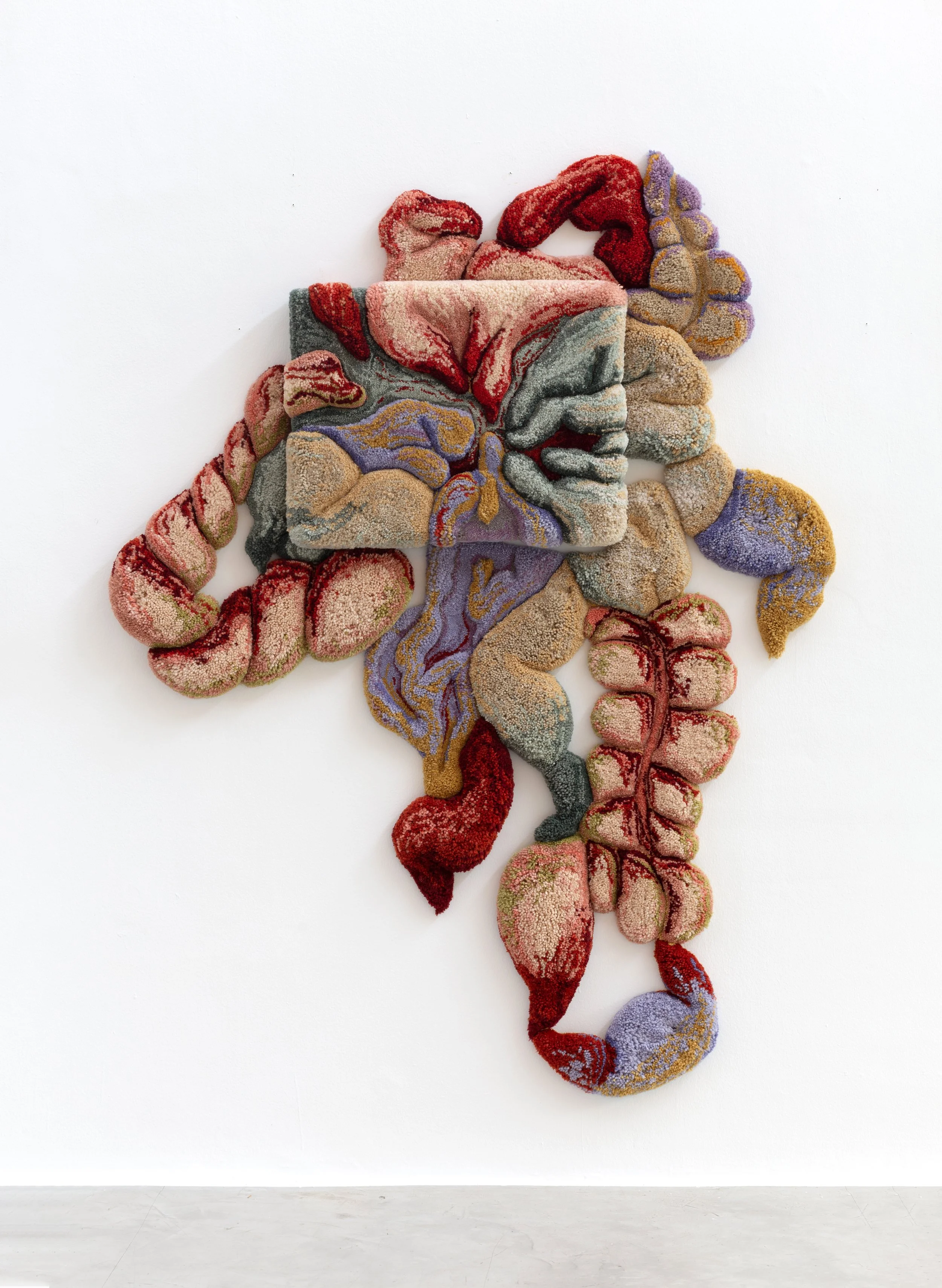

The artwork presented at the Prize is part of a series titled "Sobejos." "Sobejo" is a Portuguese word meaning surplus or excess. This artwork explores and questions the boundaries of art, as well as the traditional hierarchy between fine art and craft. At the center of the piece, a rectangular form symbolizes a hidden frame, suggesting that the rug transcends the traditional iconography associated with painting.

The abstract organic forms on the tapestry intentionally invite multiple interpretations from viewers, appearing as living organisms that fill and occupy space. These forms are deeply inspired by the internal structures of the human body: visceral, layered, intimate and speak to what connects us beneath the surface.

How do you see your work fitting into the context of contemporary craft on an international stage?

At a time when craft and art are undergoing significant revisionism, with new narratives challenging established canons, my work seeks to contribute to these conversations by offering alternative approaches that connect heritage and innovation, through a perspective rooted in my own context: a Latin American point of view. In doing so, I hope to challenge certain stereotypes and expand expectations around what Brazilian production can be.

International recognition is crucial, as it helps amplify voices and perspectives from regions like the Global South, fostering a more diverse and inclusive understanding of contemporary craft on a global scale. Through this, I aim to expand the possibilities of textile-based expression beyond traditional frameworks and geographical boundaries.

Your work feels deeply rooted in tradition yet very contemporary. How do you

balance heritage and innovation?

I work with an ancient technique, but what makes it contemporary is the way I approach it: the tools I use, the narratives I explore, and the aesthetic of the tapestries themselves. I hold deep respect for the legacy of textile practices, especially the labor of so many women, often anonymous and invisible, who preserved these techniques over time.

Historically, tapestry in the art world has been a mediated process: the artist would design a painted cartoon, which was then passed on to a team of artisans (frequently women) who were responsible for executing the piece. In this structure, the intellectual and the manual were separated, and the makers were rarely acknowledged for their work.

In my practice, reclaiming this space: the artisan becomes the protagonist, merging conceptual authorship with technical expertise. I'm interested in collapsing the hierarchy between head and hand, bringing visibility to the act of making as a form of knowledge and presence. That, to me, is where heritage meets innovation.

How important is it for you to preserve or reinterpret Brazilian craft techniques in your practice?

In Brazil, craft techniques are often associated with a context that blends heritage preservation with a deep connection to livelihood. Because of that, I feel a great responsibility when using techniques like tapestry in my work. Many women engaged in this labor in a compulsory way, so that it could eventually reach me, where I now approach it in an artistic context, by choice.

For me, it’s not just a technical or conceptual decision; it’s a way to affirm bodies, gestures, and experiences that have been historically overlooked. To reclaim a practice shaped by gendered labor and structural invisibility, and to insist that what was once confined to the margins now demands space at the center.

You were recently part of an exhibition at the Museo Thyssen. What was that

experience like for you?

It was my first time presenting my work in a museum outside Brazil, so I was both excited and deeply honored. Especially to have my pieces shown alongside such an important collection, which includes works by artists like Caravaggio and Van Gogh. Sometimes, when I think about it, it still feels surreal.

Being there marked an important step in my career, particularly in terms of reaching a broader audience in a city as international and culturally significant as Madrid.

How do audiences react to your work—especially those unfamiliar with textile or fiber-based practices?

From the viewer’s perspective, I believe the first impact of my work is always its materiality. Even when my work carries a theme or a narrative, what reaches the viewer first is the textile itself: its texture, the tactility and familiarity. Textile is never a neutral medium; it carries emotional boundaries and symbolic weight that speaks directly to the memory. Unlike other materials that may have achieved a kind of conceptual neutrality within the art context, textile remains deeply embedded in everyday life, in domestic spaces, in gestures of care, in personal history. Because of that, even those unfamiliar with fiber-based practices often feel a spontaneous connection.

There’s a sense of recognition that doesn’t require verbal explanation. This closeness is powerful, but it also reveals something about how textile is perceived in the art world. It raises questions about categorization: why must we label it as “textile art”? Why must the technique define the work? These reactions reinforce how charged this material is. It carries meaning before the concept is even named, and in that way, it speaks first.

What are you currently working on? Any upcoming projects or collaborations

you’re excited about?

At the moment, I’ve started a research that explores my ancestry, particularly through the women in my family who worked with traditional textile practices.

This investigation is especially connected to the part of my family that lived in Pernambuco, in the Northeast of Brazil.

I'm also developing new pieces for upcoming art fairs in Brazil, including ArtRio, one of the most important fairs in the country, held in Rio de Janeiro. At the same time, I’m exploring opportunities for international artist residencies. I feel it's the right moment to open myself to other contexts beyond São Paulo and let new environments influence my practice.

What would you like people to feel or think when they encounter your work for the first time?

When people encounter my work for the first time, I hope it resonates beyond concepts or fixed definitions, reaching them on a more subjective level. By working with abstraction, I deliberately leave space for multiple interpretations. I want the viewer to be invited into a place of questioning, to reflect not only on the materiality of the work but also on the context in which it is situated and the way it is presented.

Ultimately, I hope my work opens a dialogue about the potential of textile to communicate across histories and cultures, revealing how this medium can be a powerful tool for contemporary artistic expression and critical reflection.

And finally—what does “craft” mean to you in 2025?

For me, craft means community. It’s a space where I have always felt embraced, free to experiment, and able to work with my own sensibility. It’s where my hands, mind, and heart feel connected.