Color, Flesh, Machines: A Conversation with Rafa Silvares

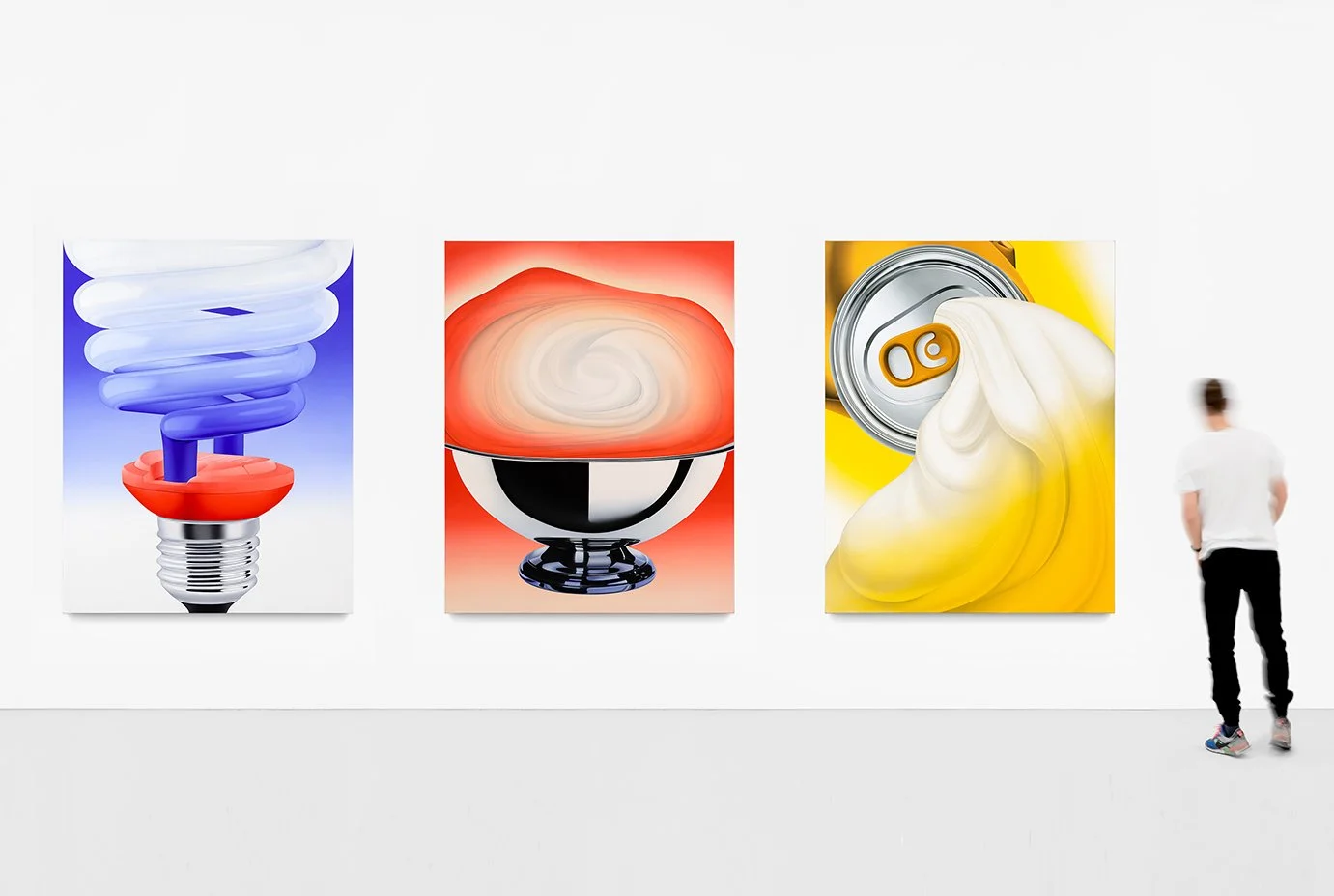

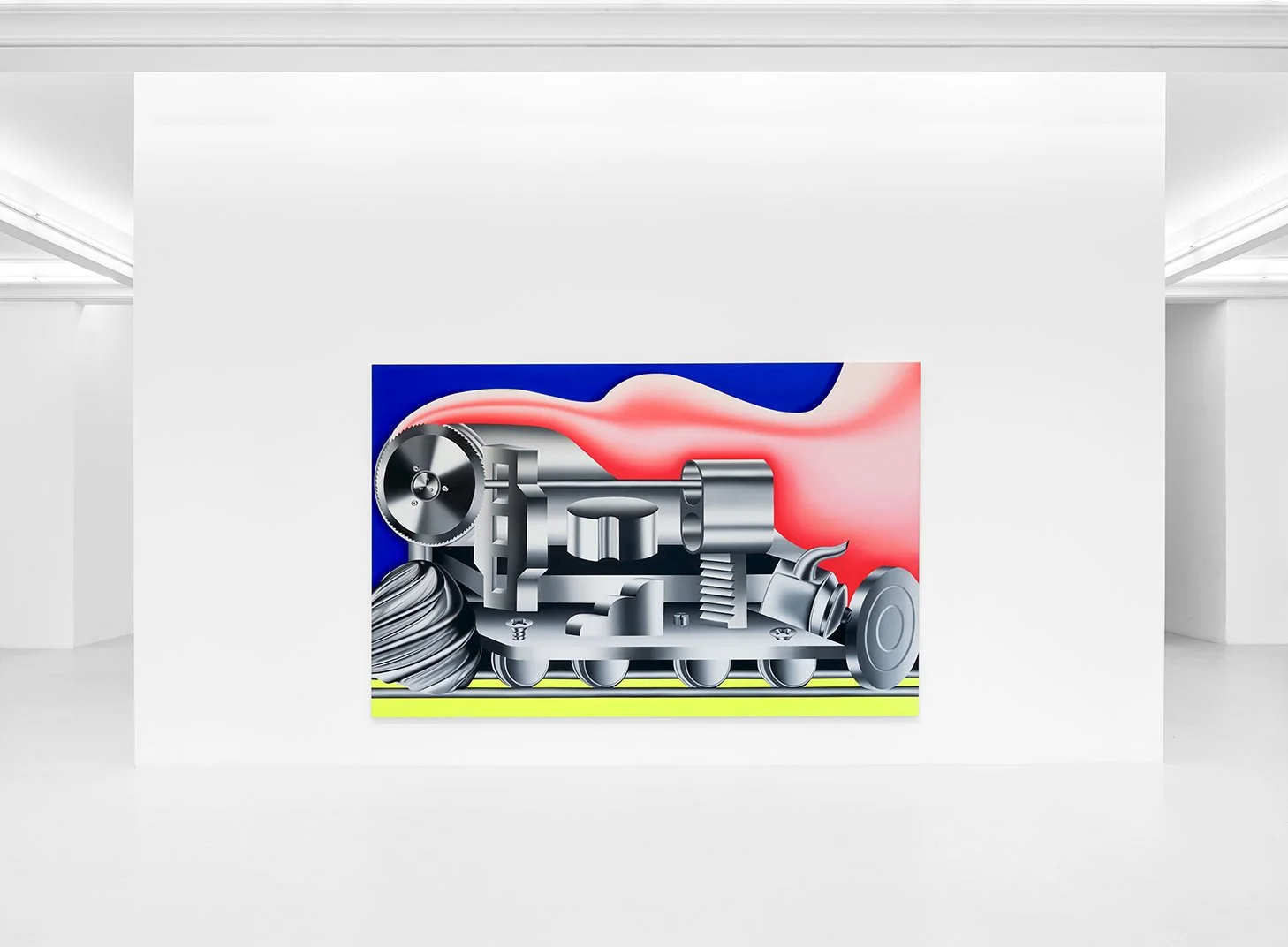

Born in Santos, Brazil, and trained in fine art, literature, and language in São Paulo, Rafa Silvares draws from an eclectic past as a DJ, illustrator, and designer. His paintings fuse industrial objects, vivid gradients, and surreal sensuality into a distinct visual language. In this conversation, Silvares reflects on his evolving practice, the influence of color theory, and how he builds strange yet seductive “rides for the eye.

You were born in Santos (Brazil) and later studied fine art, literature, and language in São Paulo. How did those early experiences – especially working as a designer, illustrator, and DJ – shape your decision to focus fully on painting?

I’ve always painted and drawn, but for some reason, it took me a while to see myself as a painter. In my mind, it felt like something I had to earn.

So, I spent many years working as an illustrator of textiles and as a DJ in São Paulo. Working on these jobs was so free, intuitive, and dynamic—mixing imagery, styles, scanning, printing, cutting, and combining words with figures on T-shirts, all while exploring various visual themes. In music, I mixed different beats to make people dance for hours.

Later, I started assisting painters, cleaning materials, and making color palettes. When I began painting, the word “illustration” was used to diminish a painting among a specific group. Good paintings were supposed to look like “paintings”. It didn’t take long before I realized that this was quite the opposite of what I was interested in.

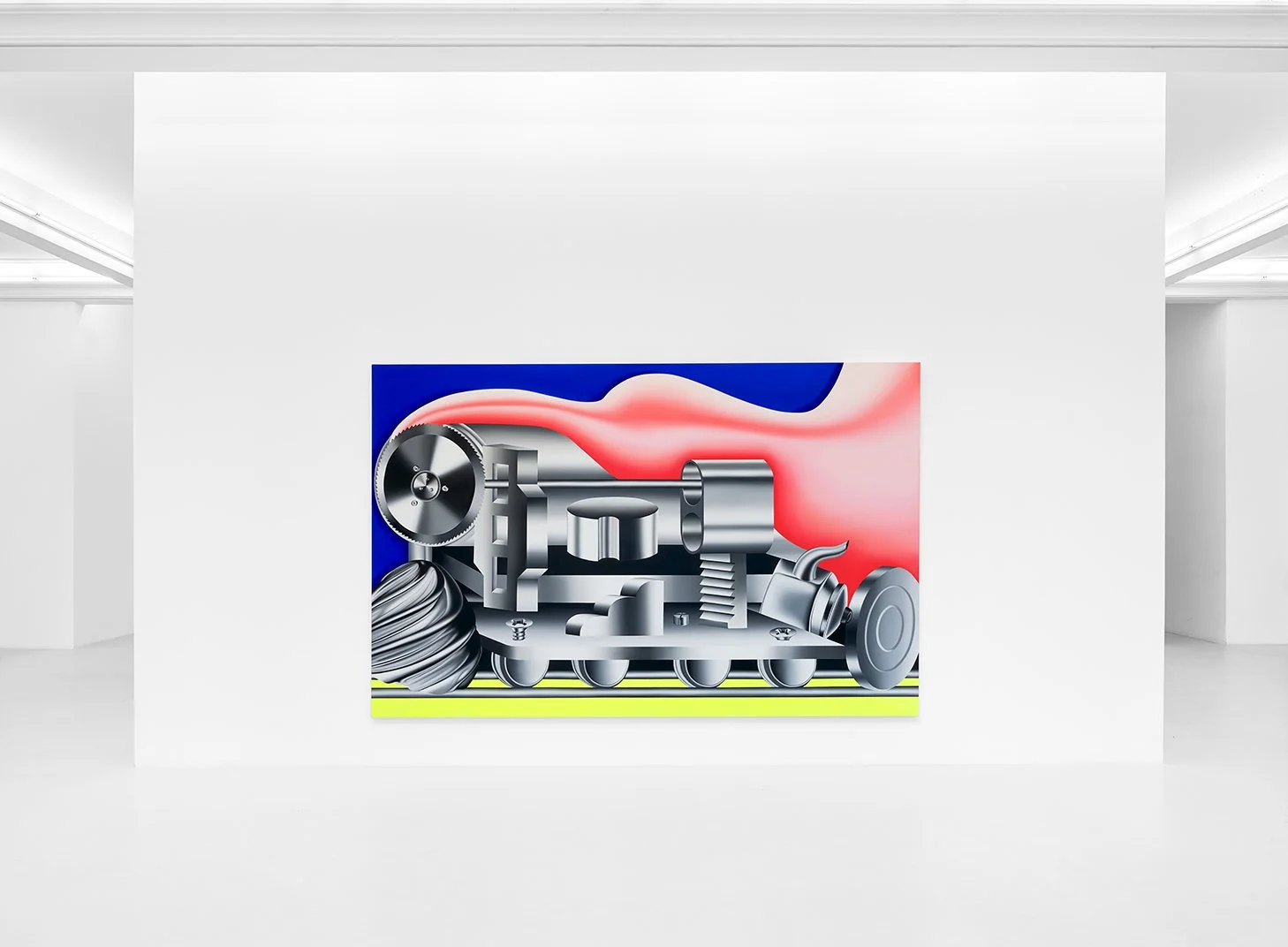

Your work often transforms everyday industrial objects—garbage cans, pipes, steaming vessels—into surreal pictorial entities. At what moment did you begin to see the artistic potential in these utilitarian forms?

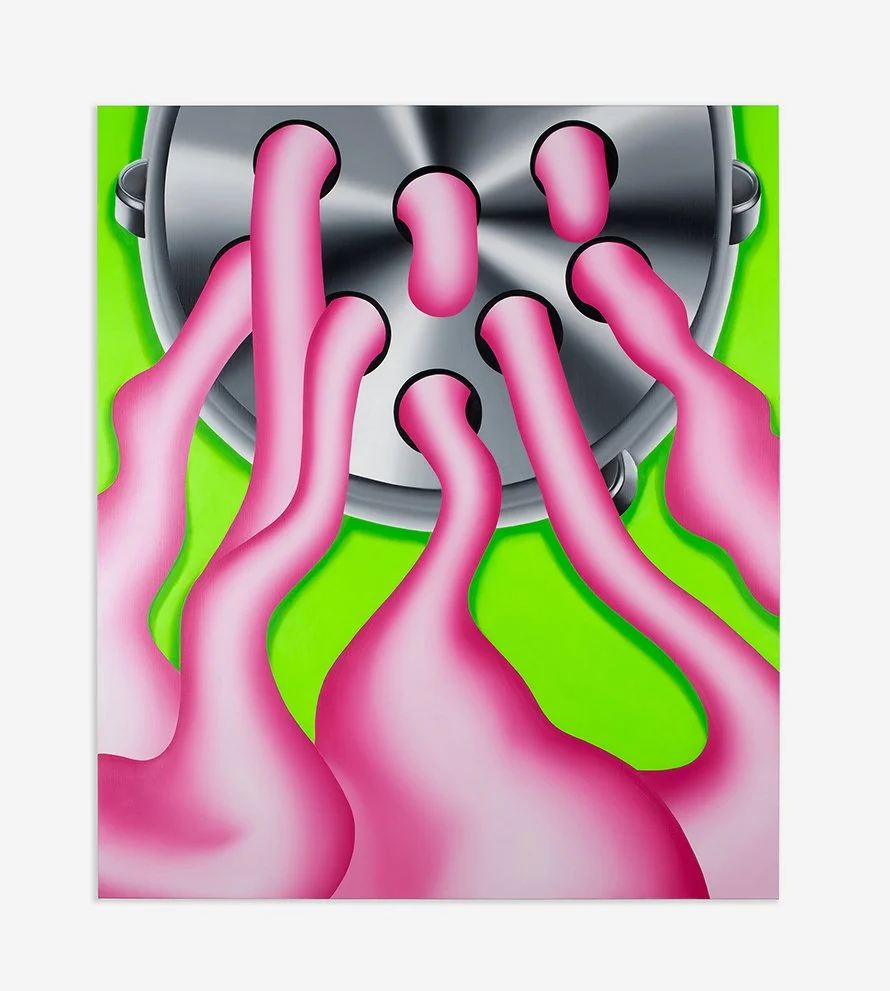

They came to me when I started painting more figuratively. In a painting class I took, there was a requirement to paint only with a grayscale palette for a while, and metal figures were a fun way for me to practice, as I could create good contrast through reflections.

Glass, for example, wasn’t as enjoyable to paint because the tonal differences on its surface are very subtle, and that frustrated me. So, it’s not so much about being utilitarian or industrial for me. There’s something about the surface of certain materials that makes me want to explore them in a painting.

You once referenced Mayakovsky’s “A tragedy” and the idea of objects rioting against humans. How does this sense of role reversal or autonomy drive your work today?

Some ideas, poems, and works in general allow me to see the world differently or more broadly, but I'm not sure to what extent they influence my work thematically.

Reading Paul B. Preciado, for example, gave me new insights into the symbiotic relationship between humans and technology, humans and substances, and the Pharmacopornographic system in which we are supposedly embedded, as well as the production of a collective Orgasmic force.

Today, I would say that the idea of machines having sex, or machines that provide pleasure—like the Orgasmatron in the movie Barbarella—is very appealing to me. These themes float around me, but I don’t intentionally aim to depict them specifically. Ultimately, what motivates me in paintings is color, shapes, and lines.

Colour plays a dominant role in your paintings—with bold contrasts, gradients, and an almost visceral quality. Can you tell us more about how colour communicates beyond the visual, perhaps through materiality or phenomenology?

Some works on color theory and phenomenology that influenced me early on still resonate with me today, such as “The Interaction of Color” by Josef Albers, “Phenomenology of Perception” by Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and “Aspiro ao grande Labirinto” by Helio Oiticica.

I believe these texts helped me see color in a more embodied and lively way. Color as something that can heal, that can upset, that can inject vitality, that can signal, and that can drastically influence emotions. Color as something that affects the whole body, not just the eye. And so on.

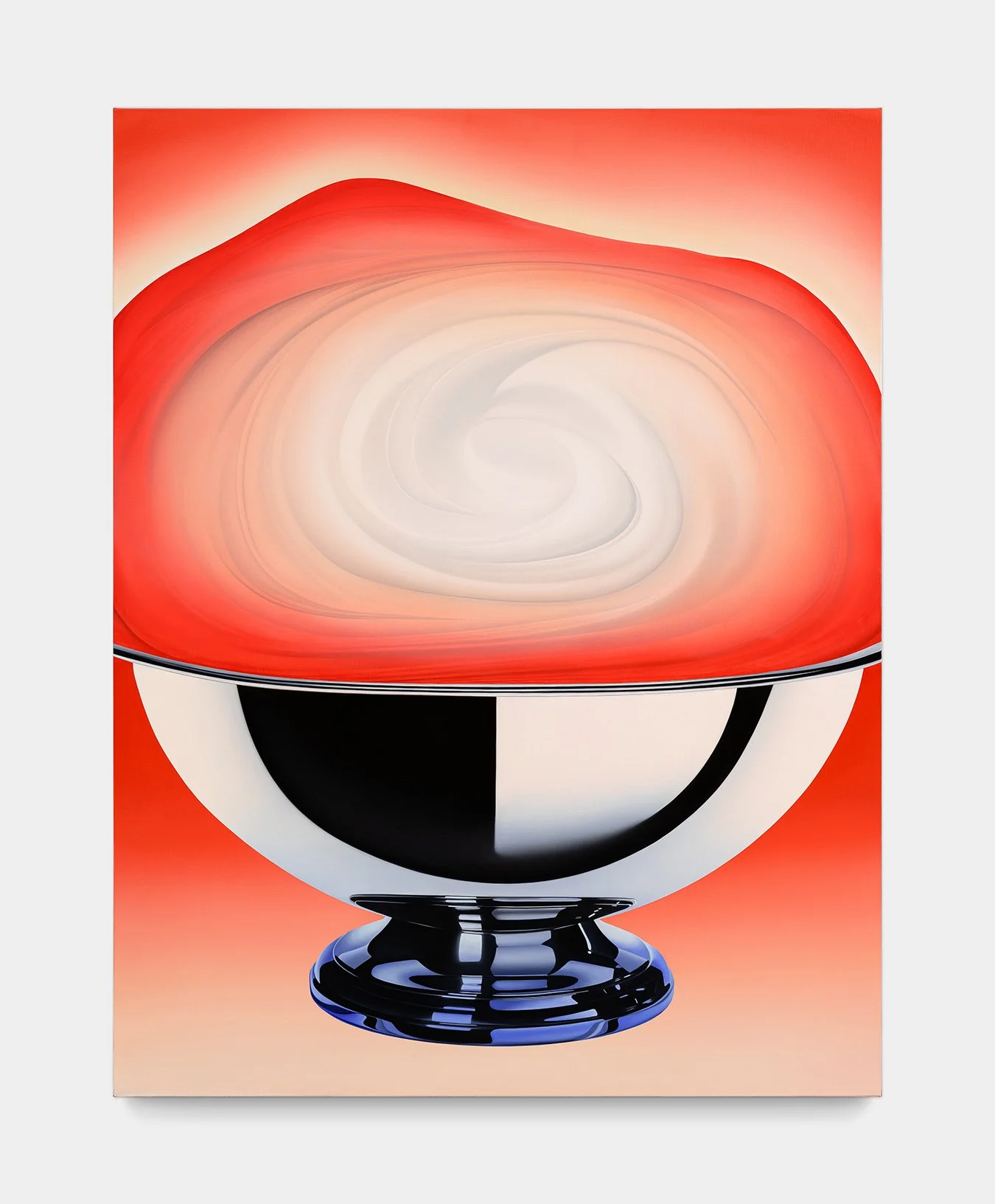

My first oil paintings were very geometric and mostly felt like color studies. Over time, they began to loosen up a bit. I would say my current work is a strange mix of control and fluidity, tension and release, with color playing a key role as a source of frequency and energy.

You’ve described your studio as a ‘laboratory’ or ‘operating room’, where the canvas is 'fractured' by the brush like a scalpel. How does that clinical approach translate into your layering and blending techniques?

I see the studio as a lab for color, but when I paint clean lines, edges, contrast, and smooth gradations, I’m thinking about how the viewer’s eye will move through the painting. I avoid sticking to formulas or locking into specific methods because, for me, they are just tools to produce a good ride for the eye.

Your work bridges diverse influences: German constructivism, De Stijl, German painters like Konrad Klapheck, alongside Brazilian concrete and neo-concrete traditions. How do you balance these formalist and historical references with your own inventory of everyday objects?

It’s not forced. I enjoy playing hide-and-seek with historical references; if they truly make sense, they’ll find their way back to me.

You’ve mentioned Duchamp’s Tu m’, Dada, futurism, metaphysical painting, and even early Renaissance artists like Masaccio and Fra Angelico. Is there a single piece, artist, or art-historical moment you return to again and again in your mind or process?

Fra Angelico’s Annunciation is a painting that sticks with me. I finally had the chance to see it in person in Madrid recently. Some paintings keep appearing to me repeatedly.

The works of Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf, for example, are like living beings. I recall a trip to New York in 2013, where I was wandering around the city and unexpectedly came across their murals and paintings in hidden spots. I then ended up dancing in Kenny’s Cosmic Cavern in Brooklyn.

Your solo show Smoked Ham in Berlin launched an ongoing ‘vocabulary’ that you intend to revisit. Could you talk us through some key pieces from that show and how they’re evolving for your upcoming projects?

In this exhibition, there was a painting I really like, which references Fra Angelico’s Annunciation. Among the works exhibited, flesh was one of the targets of my pictorial interest.

I recall thinking a great deal about how flesh is depicted in sacred paintings and Brazilian Baroque sculptures. In these works, flesh is seen as torn, pulsating, and full of expressive qualities. So, I tried to visualize flesh today, and the result was a voluptuous, sensual, cosmetic-like, smoothly blended element that has no wrinkles.

A piece of ham with a smoky eye effect. I notice that these interests continue to shape my current paintings in various ways.

You balance a disciplined daily routine—coffee, dishes, vacuuming—with bursts of late-night studio intensity. How do you manage those ebbs and flows, and do you feel they feed into the energy of your work?

Some adjustments were needed, lol. It took me a while to realize that the timing of painting is very different from mine and the world’s.

Being committed and finding balance are key, but rigid discipline isn’t the best way for me to navigate it. I now have a better understanding of the cycles of the paintings, so I’ve been able to work with them more effectively.

You’ve described generating lists—names, sensations, objects—that form constellations of ideas. Where does this process usually begin (a book, film, urban observation?), and how do you know when a constellation is ready for the canvas?

The images and lists stored on my phone are a clear way to chart this constellation of interests. Being able to visually navigate to where your mind was 2 or 3 years ago in seconds, along with finding specific paintings seen in a museum, notes, and audio recordings, are useful tools. It’s a good starting point, but filling the space of a canvas is a different game. Recently, I’ve been paying more attention to how the surface tells me what works and what doesn’t.

As you continue building your visual vocabulary through industrial objects and colour experiments, where do you see your work heading next? Are there new media, scales, or forms you'd like to explore?

I'm quite intuitive, so it isn't easy to predict. One thing is certain: the process of magnetizing ideas, figures, and creating visual associations is quite empirical and a fascinating part of making a painting for me.

I wouldn't delegate all of this to an AI to do the math, for example. On the other hand, VR and AI tools can be helpful for specific parts of the process, much like digital collage, vector illustration, and drawing. Recently,

I've been trying to find balance with my compositions. The element of shift feels more present, expressed through color gradation and movements such as circles, waves, swirls, and spirals.

Finally, what do you hope viewers take away from experiencing your work? Is it humor, criticism of everyday life, an invitation to rethink material routines—or something else entirely?

Well, it can really be all or none of those things. When I’m in the presence of a work of art, I try not to focus too much on the context or themes behind it.

I always try to sense if there’s a soul there. Most of the time, I don’t really like it when the work forces a specific way of being perceived. Although most viewers want to know what the work is about - we do have that fixation - I don’t think it’s fair to impose anything on the viewer. If I could, I’d love to get away with just providing a nice ride for the eye.