The Tremor of a Hand: Cathrin Hoffmann on Texture, Identity, and Survival

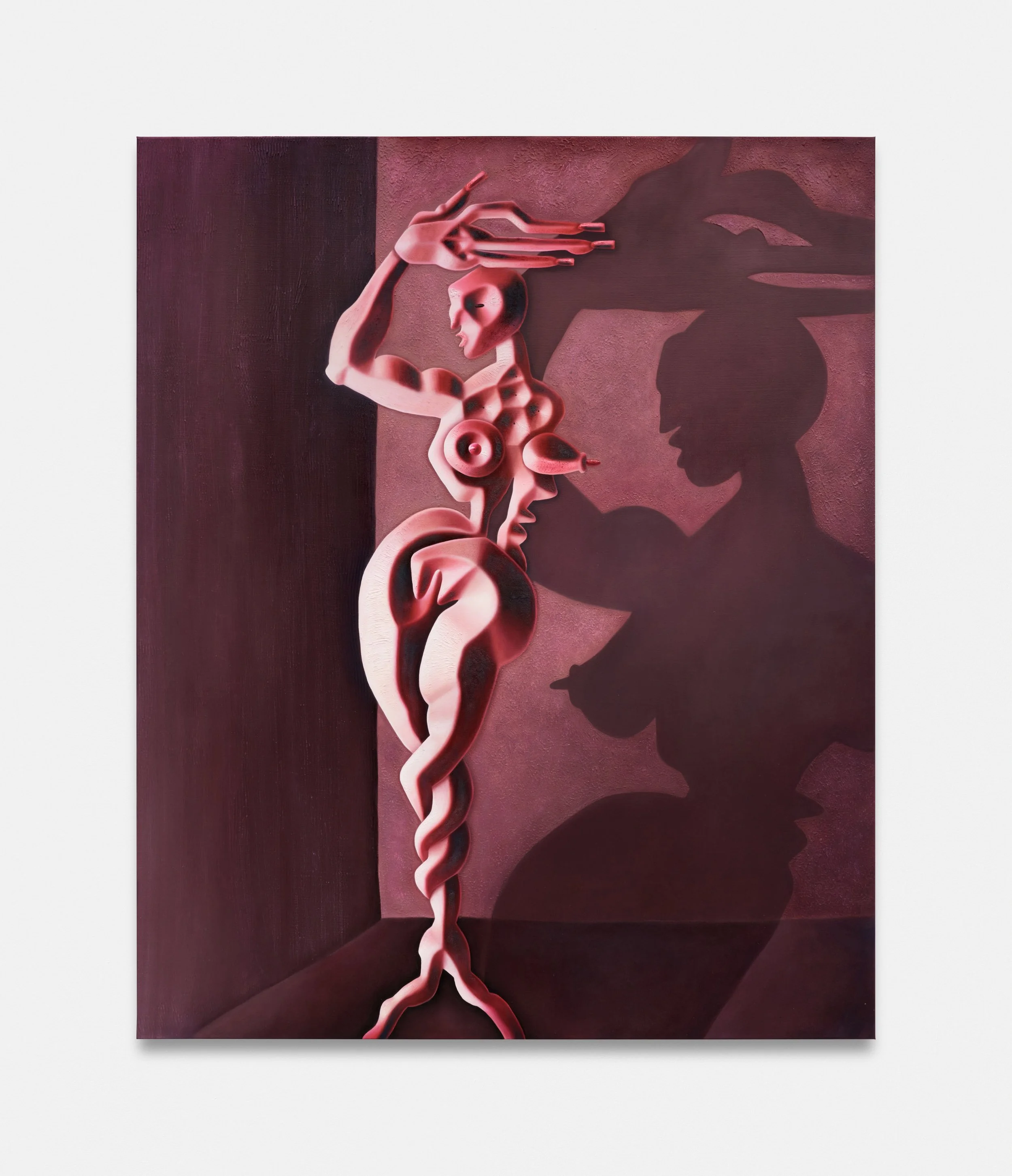

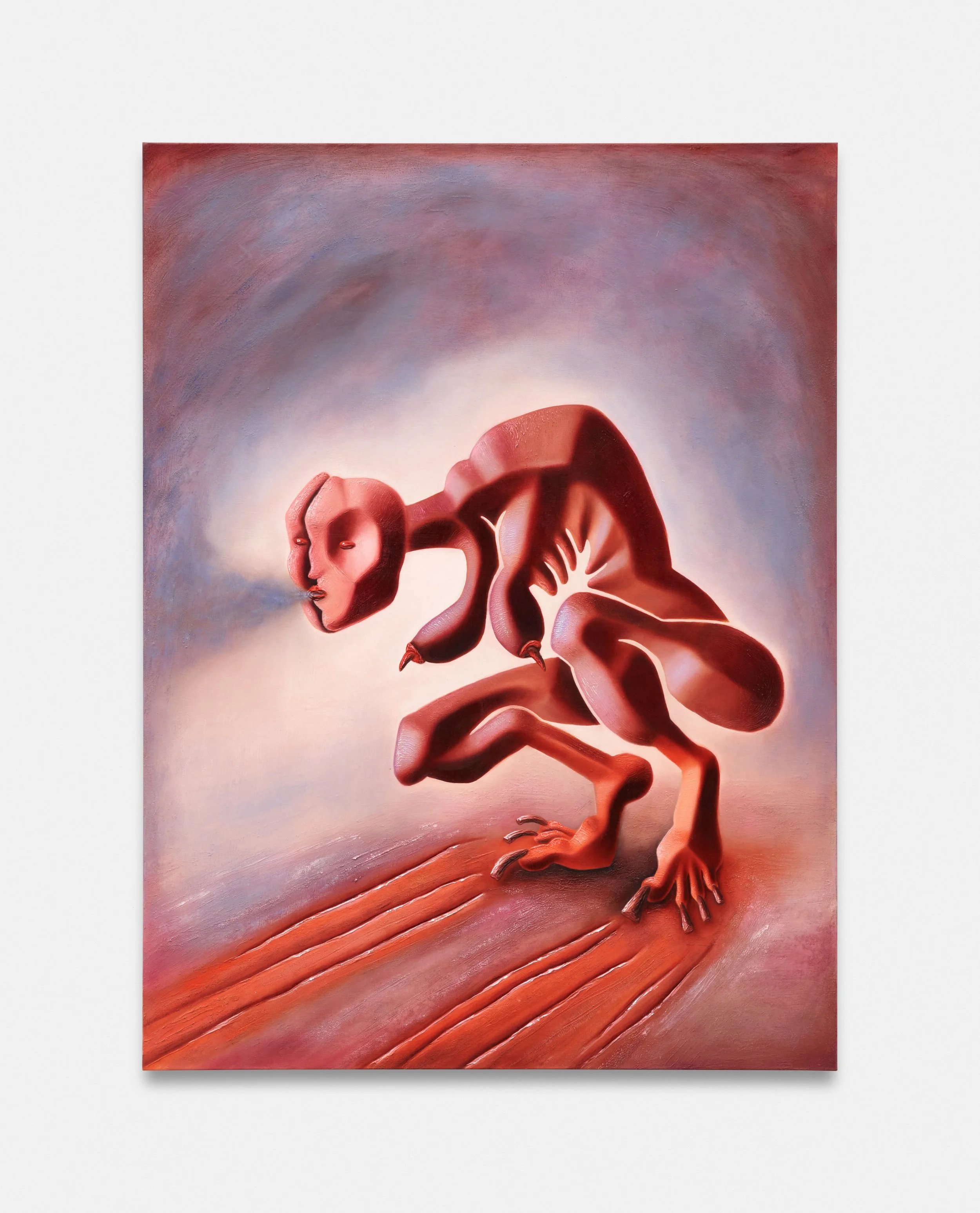

Cathrin Hoffmann’s work pulses at the threshold between flesh and code. Her hybrid figures, stretched, wounded, resilient, seem to carry both the weight of history and the dissonance of a digital present.

Largely self-taught, she has forged a language that blends oil painting with sculptural texture, collage, and installation, confronting what it means to be human in an age of acceleration. Born to German-Iranian parents and now based in Berlin, Hoffmann threads questions of vulnerability, identity, and materiality through her practice, while drawing on thinkers from Hannah Arendt to Erich Fromm.

As she prepares to curate MAXIMAL during Berlin Art Week 2025, Hoffmann reflects on her trajectory, from DIY beginnings to large-scale collaborations, and on why, in the end, the tremor of a hand or the raw surface of skin may still burn brightest.

Your work often reimagines the human body through a post-digital lens, teasing apart what it means to be flesh in an age of code. Where did this fascination begin for you, and how has it evolved as digital culture accelerates?

For me, the body is like the ultimate test of reality. It’s what pulls us back into the real analog world. In an age that’s increasingly filtered through the digital, I’m struck by the tremor of a hand, the quickening of breath, a racing heartbeat.

My figures embody both fragility and an inner strength, I’d say. I paint skin, wounds, shadows, because that’s where the human burns brightest. The faster the digital world moves, the more I’m drawn to the raw, tactile feel of texture on canvas.

You’ve described yourself as largely self-taught—learning oil painting via YouTube and experimenting with collage, installation and wall paintings early on. How has that DIY approach shaped the risks you’re willing to take in the studio today?

Not knowing felt like freedom. It helped me a lot at the start, after leaving my old life behind. There was no right or wrong, everything felt right as long as I felt free. I didn’t know the art market, only what art did to me personally.

I sometimes wonder what would have happened if I had studied art formally, but I believe that taking the long way around was essential. Things look different now. I understand the rules of the game, and I’ve educated myself in art history. While this opened many new doors in my mind, others have closed forever.

In several recent sculptures and 3D renders, bodies appear stretched, spliced or hollowed out, yet strangely resilient. What role does vulnerability play in the formal decisions you make?

I believe that vulnerability is at the core of being human. We’re not only vulnerable, but also capable of wounding others. Recognizing this opens the possibility of truly seeing one another and creating connection. In truth, we always move between autonomy and vulnerability. They shape each other.

Vulnerability means openness, to trust, to resonance with others, to being touched by the world, for better or worse. It’s never private, it’s always shared. It’s tied to power, to dignity, to the very idea of trust: to trust is to accept being vulnerable. Vulnerability isn’t a flaw in human life. It’s the very source of living together, I think.

You were born in Rotenburg (Wümme) to German-Iranian parents and are now based in Berlin. How do those layered cultural perspectives feed into the hybrid figures we see in your paintings?

I grew up in a small German town with a Persian mother and a German father. On paper I was German, carrying a German name, but my appearance told another story. People often treated me as if my very name was a lie. My mother, who was even told by the German environment not to pass on her own culture, tried so hard to integrate that it reached me only in fragments.

We siblings never learned Farsi, and we lived almost entirely within German culture. That left me caught between worlds: in Germany I was marked as different, and within my Persian family I couldn’t communicate. Even there, where I looked like everyone else, I felt like an outsider. It’s only in my thirties that I’ve begun to really explore what identity means for me.

Philosophy—particularly existentialist thought—seems to hover around your imagery. Which writers or thinkers are quietly sitting on your shoulder while you work?

I’d say Hannah Arendt is a thinker who’s been on my mind a lot. Even though she didn’t really see herself as a philosopher, her ideas about politics, responsibility, and human behavior resonate deeply with me.

I’m also drawn to Erich Fromm, particularly his thoughts on human nature and our capacity for connection. And more personally, I find Adelheid Duvanel’s writing really compelling. There’s a fragility and intensity in her work that I often feel echoing in my own practice.

Let’s talk materiality: many of your surfaces look scorched, torn or melted. What experiments, successful or disastrous, have most expanded your palette of textures lately?

I’m increasingly trying to bring out texture from the smooth oil surfaces. Lately, I’ve been drawn to the contrast between a digital-like aesthetic and a rough, sculpted surface. I’ve started building my paintings with layers of gesso, working almost like a sculptor, while the final layers are super-thin glazes that make the colors pop.

My process begins with an intuitive sketch, then moves into a carefully considered, almost digital compositional stage, and finally embraces the freedom and unpredictability of the materials. Since I’m not formally trained as a painter, there are often moments in this process that escape my control, and I actually like it that way.

Collaboration is woven into your practice, from podcasts to joint shows. After co-presenting Hardest Kinds of Soft with Céline Ducrot at Kunsthalle Gießen earlier this year, what surprised you most about sharing authorship?

The exhibition with Céline is a great example. During the preparation and exhibition, we became friends, and I think I can even speak for her when I say that at first, neither of us really believed our paintings would fit together. It was only through the process of conversation and sharing our ways of thinking that I realized how well our work actually complements each other.

Our visual language might be different, but what we experience and feel has many similarities. I really enjoy collaborating with others because it teaches me a lot about myself. Working with others has shown me that my own paintings are never really “just mine“, they only come alive through someone else’s gaze. At the same time, I've noticed that curators often find my work too intense on its own and prefer to pair it with a more tranquil counterpart.

While I understand this, I also find it somewhat frustrating, because just as my work evolves and recharges with another work, it also makes compromises. I think it's important for viewers to experience my work on its own, without any buffer, even if it's too extreme for some.

You’ve mentioned that time spent in Nicaragua working twelve-hour days unlocked something vital for you. How do residencies or periods of dislocation continue to rupture your habits?

I really enjoy the residencies. I’m not someone who can stay in a daily routine for too long. I need change and challenge, especially in terms of place and culture. Every residency opens up horizons for me that I couldn’t reach before.

Even though it’s often stressful, with deadlines and constant pressure, I actually enjoy that. Maybe I even like the feeling of being a little out of place. Without these breaks, I’d probably just get stuck in my own patterns.

Many viewers say your figures feel both alien and deeply human. Do you see them as self-portraits, speculative archetypes, or something else entirely?

Maybe they are reflections, but not portraits. They carry my fears, my longings, but also something bigger than me. I see them more as archetypes. Fragile messengers of an experience we all share, in a time that challenges us with technology and makes us seem to lose touch with our authentic selves.

Soundtracks often leak into your Instagram stories. Does music guide the rhythm of your mark-making, and if so, what have you been listening to while preparing the new body of work?

I often paint in silence. It really depends on the stage of the work. I’m not great at multitasking, so I need quiet to focus.

But then there are phases where it’s all about the sheer joy of painting, the craft itself. That’s when I usually put on audiobooks or podcasts. Lately, I’ve been listening to Paul Lynch’s book "Prophet Song".

During Berlin Art Week (10 – 14 September 2025) you’ll step into the role of curator for a group exhibition you’ve conceived. What questions are you posing through the selection of artists, and how does curating alter your relationship to your own practice?

“MAXIMAL” is the name of the exhibition in a remise in Berlin's Wrangelkiez in Kreuzberg, an old building that also happens to be my studio and is soon to be demolished. The space, quietly situated between a church and a mosque, next to a disused slaughterhouse and traditional workshops, carries the district's multifaceted history within it. The exhibition brings together almost 40 Berlin-based and international artists, and in a way, the remise serves as a stand-in for all the creative urban spaces that are disappearing. At the same time, MAXIMAL reflects on how we consume art during Berlin Art Week. In just a few days, visitors encounter an overwhelming number of works. How deeply can art capture our attention, and what happens when it disappears completely?

Looking a decade ahead, what would you like viewers to feel when they stand in front of a Cathrin Hoffmann piece in 2035—terror, tenderness, or something we don’t yet have words for?

I just hope we’re still able to feel, to not get completely numb from all the constant distractions and bombardment, all the fake news and noise we’re swimming in these days. Beyond that, it doesn’t really matter what we feel. The main thing is that we’re still capable of listening… especially to our inner selves.