Unveiling the Human Psyche: Interview with Coady Brown

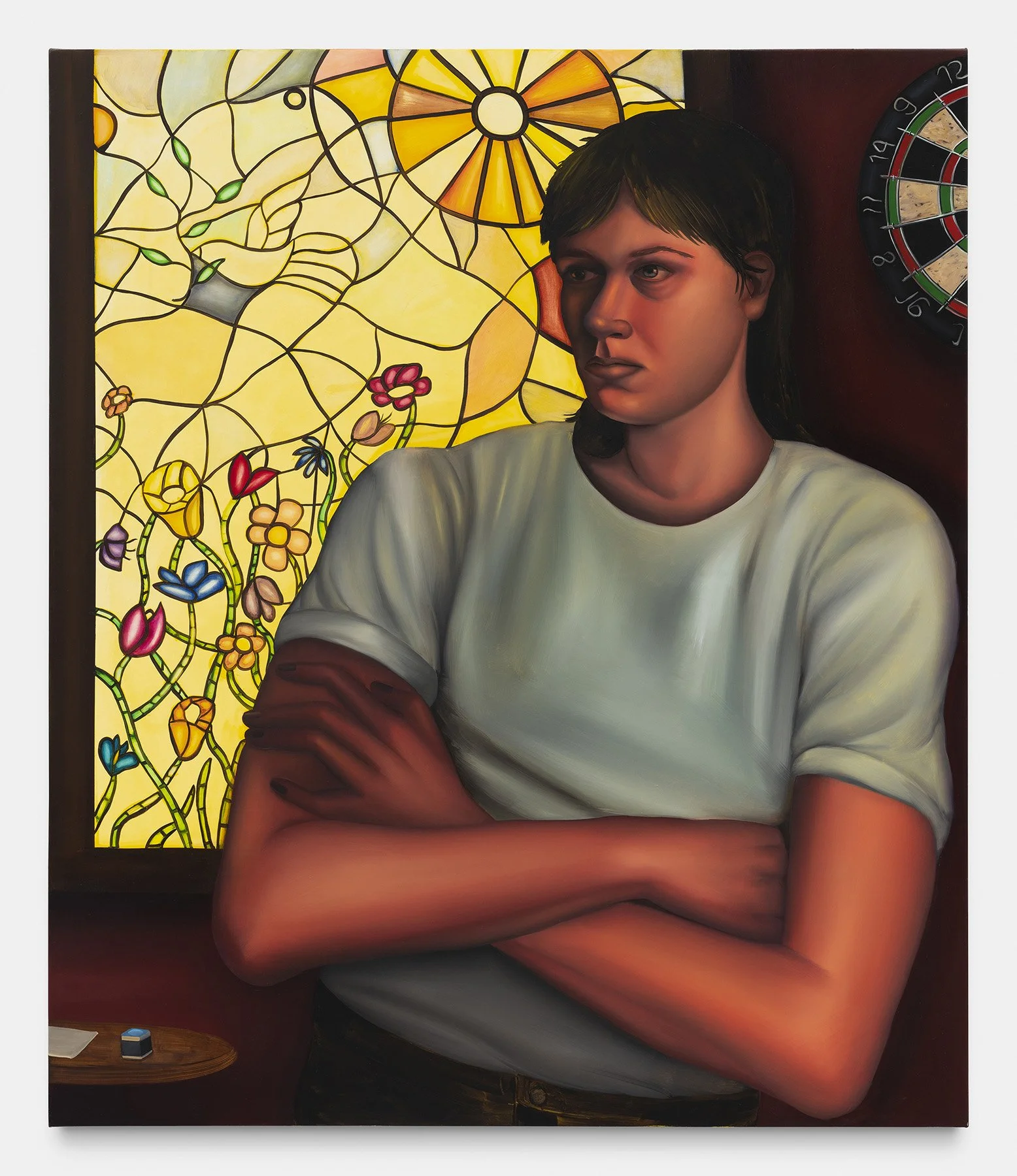

With canvases that oscillate between tenderness and tension, Coady Brown captures the fragile complexity of human intimacy. Known for their saturated palettes, distorted perspectives, and figures caught in moments of vulnerability, Brown’s paintings invite us into spaces where desire, identity, and emotion collide. Based in Philadelphia, the artist has quickly emerged as one of the most compelling voices of their generation, exhibiting internationally and drawing attention for their ability to transform the personal into the universal.

In this interview, we dive into Brown’s process, influences, and the emotional undercurrents that fuel their work — from the role of color as a psychological tool to the blurred line between comfort and unease.

You were born in Baltimore and raised in Cincinnati, how did this contrast shape your initial relationship with art and self-expression?

As cities, from my perspective, the two places couldn't be more different. I think things have changed a lot, but in the early 2000’s, Cincinnati was a very small-minded, segregated, and insular place.

The gift that it gave me was knowing that if I wanted to be around the type of people that would enrich me artistically, I needed to work hard to go and do something with my life.

I had a small group of friends who felt the same way- one even left high school and started college at 16. The underlying sentiment was always: get the hell out of here. Which really adds fuel to your fire when you are a teenager. It made me hungry.

You studied at Tyler School of Art (BFA) and Yale (MFA). How did each institution influence your artistic development?

Tyler was where you were really thrown into the deep end as an artist. You weren’t necessarily “taught” things in a demonstrative way: “Mix this color with that color, this color with that”. My first painting teacher was the legendary Dona Nelson, who on the first day of painting class had us take all of our supplies and giant canvases and start plein air painting on the windy campus sidewalk.

It was very…..”art happens as you are making it”, not “art happens because you understand a tertiary palette”. It got you out of your head and into your body. Yale functioned similarly in that the emphasis was on quantity instead of quality. They didn't want you getting stuck on a singular project that was maybe limiting and could turn out to be a flop.

I’ll never forget a studio visit with Bryon Kim, who said: “You’re not going to like what I have to say, so I am going to leave immediately after, but I think you should make abstract paintings and videos”. And then he slowly backed out of the room. And did I go on to make those? No! But the idea was always to get yourself to try something so new, so out of your comfort zone, that you could circle back around to yourself.

You’ve mentioned being fascinated by art history and figures such as El Greco, Otto Dix, Modigliani. What about their work resonates with you today?

El Greco is one of my all-time favorite painters,the way he underlines the spirituality of his figures with the way he extends their bodies, particularly their necks and hands, into this type of spiritual distortion.

Modigliani also distorts his figures, the elongation of the neck, the sculptural faces and poses, there is an arching sexuality to the work.

Otto Dix’s work underscored the moral underpinnings, turbulent political climate, and attitudes about sex and self expression of his time. He described himself as a Realist, in that he wanted to be a reflection of the world around him, no matter how dark and depraved. He loved the ugliness. And as someone who loves beauty, I really admire that. Beauty is its own kind of trap. You can’t become too seduced by it.

How do fashion, film, and everyday observations inform the emotional and narrative quality of your paintings?

Ideas for paintings come from everywhere: color combinations, a cut of fabric, a film still, a photo I took. A coffee mug sitting at the edge of the table, the way light cuts across the yard at dusk. Very nerdy painter stuff.

My source material comes mostly from print sources: I need something tangible to look at. I have an extensive library that I am always adding to: magazines, books, catalogs. And then from that initial spark of an idea, it becomes about the emotional undertone of the painting.

Is this about loneliness, insecurity, fear, or vulnerability? The greatest gift I have given myself as an artist is the permission that any idea can turn into a painting. I think a lot of what plagued me when I was younger was a concern that my ideas were not serious or academic enough.

But anything can be the impetus for a great painting. You never know what is going to work, so if you edit yourself too quickly from the beginning, you are losing an important aspect of the process. And then if in the end the painting is bad, just get rid of it.

Your practice hinges on drawing as a starting point, often exploring pose, pattern, and composition in intimate frames. Can you walk us through that process?

I love that with drawing, and painting too, you are already starting out with a set of limitations, which is the size of the paper or canvas. So you have a framework you have to work in, a set of boundaries that can only be pushed so far.

That's why I love figuring out compositions. How many inches something is from the edge, what angle things converge from, everything contributes to the impact of the image.

I know I am ready to paint when the drawing has a feeling of solidity, that it is just right and I wouldn't tweak a thing. Drawing is critical, a way to flesh out different ideas, and different iterations of the same idea. Don’t fall in love with the first version, there might be a better way.

You’ve spoken about balancing planning with spontaneity, how do you navigate the tension between control and chance in the studio?

It’s always a tension I am trying to navigate. I think it's common for artists to look back at older work and think “Man I was so much freer then! The energy was looser, more spontaneous”.

Painting for me is about this balance of controlling energy and letting it go. Brush strokes play such a part in that. Letting certain areas show more transparency and movement, while other areas are opaque and deliberately rendered. I’ve also experimented a lot with making colorful underpaintings, and then painting over it with a darker color and scratching through the surface which leads to a lot of random discoveries. That is the balance I am always trying to achieve: random discovery meets thoughtful planning.

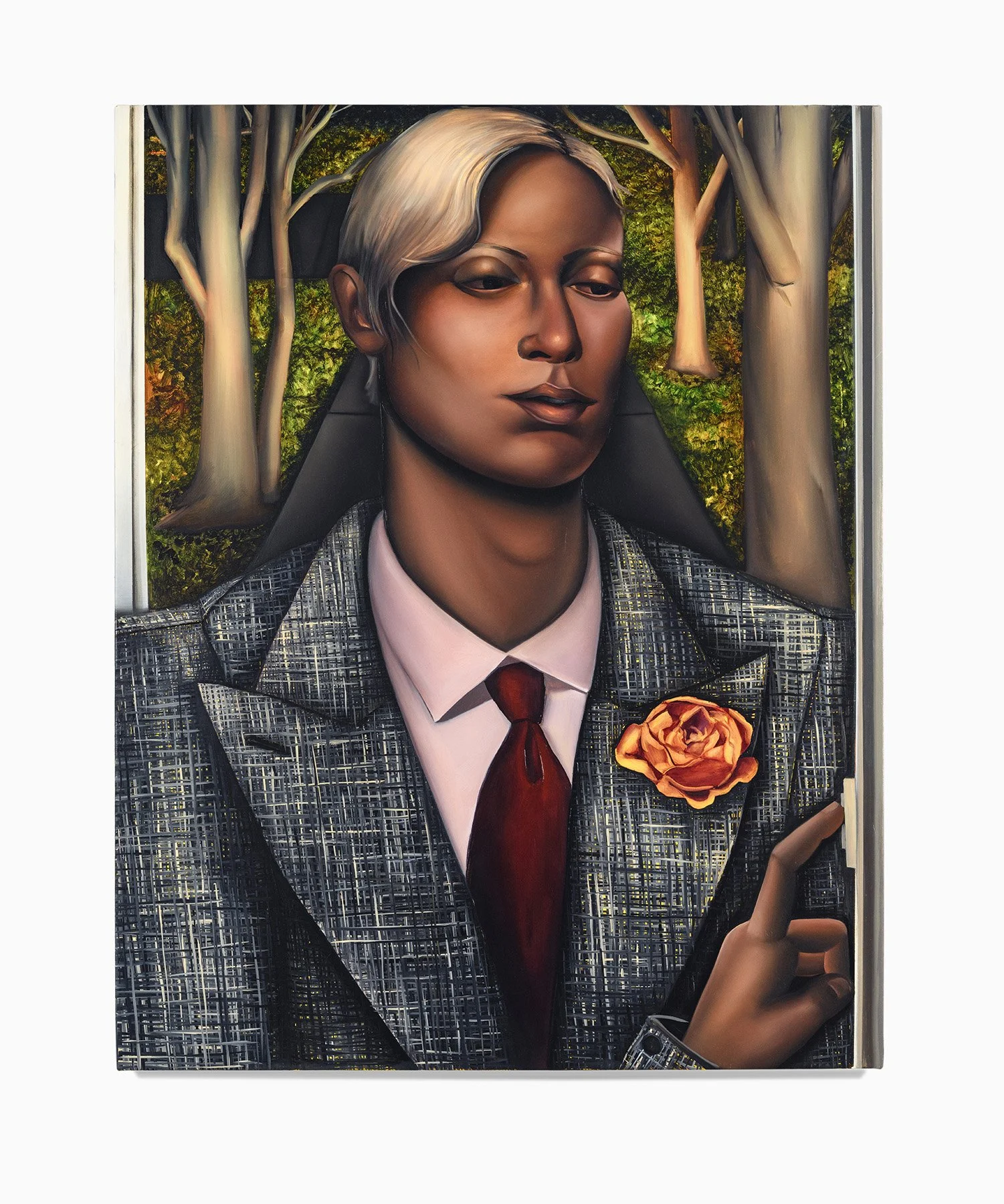

Fashion is central in your work, how do you see clothing functioning as both a site of celebration and vulnerability?

I really have no interest in the classical nude figure, I am much more interested in clothing as a reflection of contemporary society. Clothing is a form of cosplay, or as RuPaul says: “We’re all born naked and the rest is drag”.

More so than clothing even, I am interested in what different shapes do to the body. Do they hide it, expand it, compress it? Make it feel more powerful, more vulnerable, more exposed, more armored? The idea that a suit makes someone powerful, and a mini skirt makes someone more vulnerable, is a complicated dynamic. How men operate in the world versus women.The authoritarianism of one body over another.

These ideas are constant streaming thoughts. How we chose to perform ourselves. Lately I am particularly inspired by men’s fashion in the 80s, which is actually quite feminine. Very soft, preened, pleated, manicured, aware of the body, not afraid to play with proportion and exaggeration.

Your paintings often depict androgynous figures, prompting conversations around femininity and strength. How do you conceptualize gender in your portrayals?

To put it bluntly, I am not currently interested in painting men, but I am interested in masculinity. I just think women are so much more compelling subjects, particularly when there is an understanding that femininity is such a societal construct, it's a bit of a burden to bear. Again, revisiting the idea of beauty as a trap. It is something to play up or play down, to twist or contort.

Your scenes, set in bars, bedrooms, nightscapes, feel charged with psychological tension. What do you think about narrative ambiguity in your work?

The narrative is always ambiguous, almost secretive. There is a sense of what is going on, but there is rarely a full sense of clarity. I think for me it reinforces the idea that we will never truly know what goes on in someone else’s mind. That there is this level of impenetrable privacy that everyone possesses. That as an individual, we will never fully understand anyone but ourselves.

In the solo exhibition My Eyes Burned Bright, you explored the “gaze”, both observing and being observed. What draws you to this dynamic?

To me, it is the central dynamic of the painting and the viewer. As the maker, I am always aware of how the viewer is going to digest the image.

What are they going to be drawn to first, what visual cues are they going to interpret and derive meaning from. Equally as important to this, is my understanding as a woman in society, your relationship to being perceived is ever-present.

To be looked at, evaluated, and assessed continuously. I am always thinking back to the role of the female model in art history. Always something to be visually digested, with little to no resistance or autonomy.

In curating To Move a Mountain at FAWC, you included a “Bouquet” painting that moved away from figurative narrative. What inspired that abstraction?

To me, they are about making something real feel abstract, versus in most of my work I am trying to make something abstract or fleeting feel real, to concretize a feeling or mood.

So to make something from observation, a still life painting, feels like accessing a different part of my brain. It is a welcomed relief.

You’ve mentioned creating these flower works during moments of reflection amid career momentum, what do they signify emotionally for you?

The first one I made, I made right at the end of a body of work for a solo show in 2021. The group of work had taken so much out of me. We were still in the throes of the pandemic. I couldn’t attend the show overseas, so I wanted to make something that could honor the moment instead. More spiritually speaking, it was my way of expressing gratitude for being able to make the work, to have my studio as a safe haven.

Making these Bouquet paintings allows me to slow down and reflect, which is hard to do while making the figurative work, where it can feel a bit frantic. The Bouquet paintings occupy my brain in a different way.

How many pieces are in the Bouquet series so far, and how do they fit within your broader practice?

Wow I think there are 16 or so now? They are now evolving. Each one I have made symbolizes something specifically, whether it is a person, a place, or event. What each one symbolizes is something I keep to myself, it feels ultrapersonal, and a part of my practice that no one gets to fully understand but me.

With some of the newer paintings, there are floral elements that are more incorporated into the figurative work, that hold their own meaning. For my last solo show “Suitor”, there were flowers as boutonnieres, as a single stem on a vanity, and as an elaborate bouquet left on the kitchen counter. They drive a lot of the emotional content of the work, but they just appear in slightly varied forms.

You recently had solo shows in London and Los Angeles, and previous residencies like Skowhegan and FAWC. How have different spaces shaped your thinking about scale and presentation?

I moved around constantly until I was 30. I lived all over the country, for varying lengths of time. It was generative for me to always be in new environments, residencies in particular have always had a profound impact on me: they are such concentrated and meaningful experiences.

For a long time, the largest size of a painting I would make would be 54” x 46”, because that's what could fit in the hatchback of my car. But as logistical constrictions became less of a concern as my career developed, I always tried to make work the size that the image was asking for. I typically like the figures to be a little smaller than life-size, so that usually dictates the dimensions of the work.

You’ve mentioned working on larger paintings as intentional gestures. How do scale and intimacy coexist in your exhibitions?

That is something that I dealt with a lot in my most recent show. I wanted the work to be intentionally scaled down- I like it when the viewer has to get close to the image.

I was playing with some pseudo trompe l'oeil effects, and trompe l'oeil paintings are traditionally small. A figure’s reflection in a mirror, a figure standing in a doorway, I wanted the pressures of those spaces to be felt. The small scale helped with the sense of compression and density.

You’ve lived in several cities and studios over the years. How has this mobility influenced your creative rhythm and sense of stability?

Mobility was really important to me for a long time, but after eight years of constant upheaval, I was really craving stability. I wanted to work in the same place for an extended period of time. The thing that once served as fuel to my practice actually started to become a hindrance.

Moving to Philadelphia in 2020 and having the same studio for 5 years was exactly what I needed, to be able to work on something, not quite have it figured out, and then be able to abandon it for a while without thinking “OK I am leaving soon, what am I going to do with this?”.

This past year my boyfriend and I bought a house in the country that has a studio building on the property, and I can’t tell you how excited I am to have a forever studio. I even have plants in there.

What does a typical studio day look like for you now, do you follow a ritual or let the day evolve intuitively?

I wish I had more of a ritual! I am either really all over the place or laser focused and locked in. It just depends, mostly if I have a hard deadline or not. Because the studio is now steps from my front door, I usually putter around the house in the morning, have coffee with Pat, run a few errands or do a few chores. And then around lunchtime I am there until whenever I decide to cook dinner.

Now that my studio is at home, I can take a break by weeding in my garden, playing fetch with my dog, or taking a nap on the couch. It makes the work feel more integrated with my life. And it's spawning a lot of new ideas for paintings.

Your paintings evoke fleeting moments, charged with both drama and subtlety. What reactions or feelings do you hope to evoke in viewers?

I hope to evoke some sense of emotional recognition, the paintings are super-charged in a way, inspired by everyday life but with a heightened sensibility, hoping to capture how something feels rather than what something is. I think that's why I love El Greco and other Mannerist painters so much. They understood that only through exaggeration could they really get to the heart of meaning and expression.

Looking ahead, are there new themes or formats you’d like to explore in your work, digital, installation, or collaborative projects?

Now that I live in the country, I am in awe of the landscape around me. It is so unbelievably beautiful and layered. I’ll drive around and will see a cow sleeping under a willow tree- it's magical. This has brought me to revisit my favorite landscape painters: Grant Wood, Marvin Cone, Lois Dodd, Charles Burchfield, Marsden Hartley. These painters have a very sculptural understanding of topography and space, which is so evident when driving through farmland.

There are also always creatures lurking in my garden and studio: spiders, caterpillars, moths, slugs, crickets, bees. frogs, you name it. Nature is going to show up in a very significant way in my next body of work. It’s a revelation.